It was two days after my granddaughter Lilla’s first birthday. I returned home from the Bay Area yesterday afternoon after spending time with her and her family to celebrate this momentous occasion. I went to bed feeling grateful for all my healthy, happy kids and grandkids.

About three in the morning, I woke with my heart racing and stomach upset. I feared I was having a heart attack. Couldn’t be, I decided—for no other reason than I didn’t want to be having a heart attack. Probably just gas from the burrito I ate for dinner. I tried shifting into different positions, hoping that would alleviate the discomfort. After an hour with no relief, it occurred to me that this was a severe panic attack.

I’ve had mild anxiety attacks over the course of my life, but only one other severe one—on my birthday in March 2021, nine days after my husband Gary died. My son and daughter were with me and friends were bringing lunch to celebrate my achievement of surviving another year.

About an hour before they arrived, my heart started racing. I was nauseated and lightheaded. I tried to banish the feelings with deep breathing. I felt I was going to faint. I’d once read that if you feel faint, you should sit and put your head between your knees. I gave it a try. Staring at the floor, I noticed it could use a good vacuuming. I refocused on my dire circumstances and diagnosed myself with a panic attack. I staggered to a kitchen cabinet, took out my prescription of lorazepam and ate one.

The sickening feeling persisted for another fifteen minutes. I reclined on the sofa, seriously concerned I might die. I was afraid of the effect this would have on the kids. This had the potential to become one of those salacious stories told to future generations who would shake their heads in astonishment—what a horrible legacy to leave where one parent dies and a week and a half later, the other drops dead.

At four this morning, I got up and wobbled down the stairs on shaking legs to the kitchen and ate a lorazepam. I made a nest on the sofa and tried to go back to sleep. If I was indeed having a heart attack, it would be easier for the paramedics to cart me out of the house from the living room and not have to navigate the stairway from my bedroom. It would also be easier for the mortuary removal people in the event the EMT’s weren’t able to get here before death nabbed me.

I don’t know how long before my symptoms lessened and I was able to sleep. When I woke at seven, my heart no longer raced, but I still suffered what Southerners call the vapors—lightheaded and weak. I brewed coffee, hoping caffeine—that miracle drug—would make everything okay. It did not. I started drinking water, thinking maybe I hadn’t hydrated enough while traveling the day before. It took me the entire morning and several glasses of water to start feeling a bit normal.

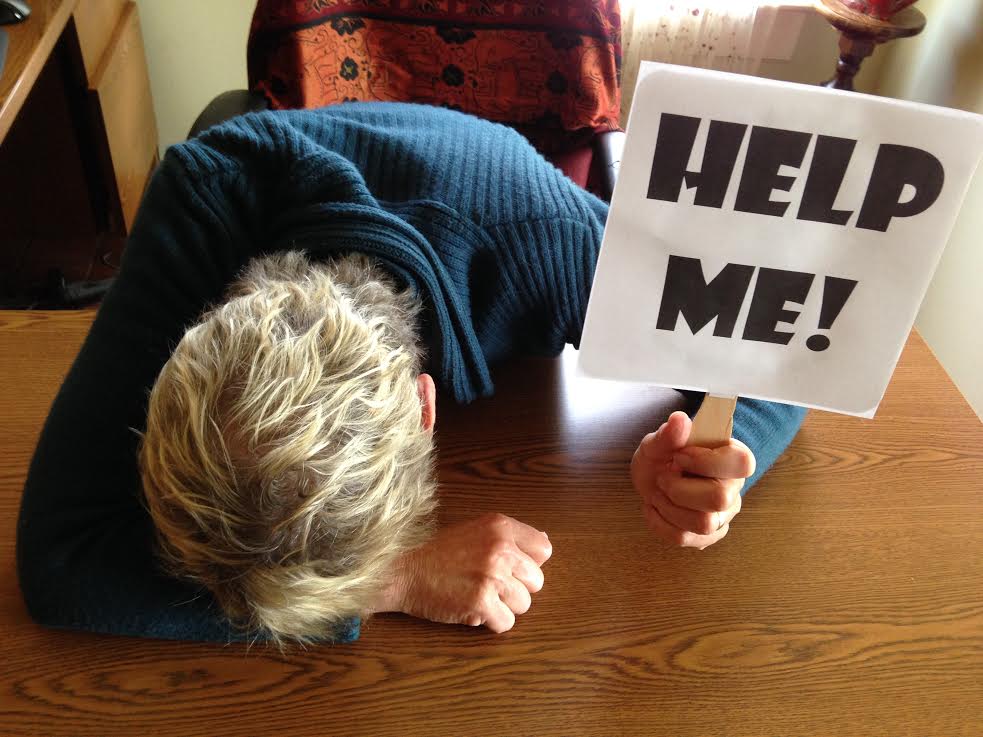

At noon I ate lunch and cleaned up the kitchen. I must confess, I’m not a big fan of kitchen maintenance. I’m perfectly content to let pots and dishes pile up for a day or so before thinking, yeah, maybe I should do something about the situation. While cleaning, I listened to Frank Sinatra’s, “The Way You Look Tonight.” I love that song and listen to it at least twice a week. It makes me nostalgic for Gary, but not sad. Today, it surprised me by bringing tears that fell into the soapy suds of a pot I was cleaning. I had to stop scrubbing, sit in my crying chair at the kitchen table, put my hands over my face and weep.

What was going on? I hadn’t had a solid weeping session in weeks. I was fully prepared to report to my therapist that I’d turned a corner and was cured from this grief nonsense after a mere 11 months. Wow, look at me, ever the overachiever. From here on out I would waltz through sunny meadows, frolicking with butterflies and chirping birds.

As I wept, I realized that my archenemy grief had been waiting for me since February 10th, the one-year anniversary of Gary entering the hospital to begin his five-week journey towards death. Every moment of his 24 days in the hospital, I worried about him being alone. It was Covid Time with no family allowed. Every moment, I worried I would get a call to say there was nothing more to be done, to come pick him up, bring him home and figure it out by myself. Every moment, I was terrified, absolutely terrified.

A few days after Gary entered the hospital, our beautiful granddaughter Lilla was born. When I got the news, I cried so hard with a combination of happiness and sadness that Gary wasn’t with me to relish the news that I thought I’d have an aneurysm. I wanted us to celebrate this new, precious life together, share our joy in person, smile with sheer delight into a Face Time call. but we could not—and there was nothing I could do to make it so.

The following weeks were a whirligig ride with an evil carnie on an extended cigarette break, unwilling to pull the stop lever. I was blessed to have family take time out of their busy schedules to be with me as we trudged through one frightening day after the other.

Three weeks after Lilla’s birth, she was loaded into a car with her two-year-old brother Parker and my brave son and daughter-in-law made their way from the Bay Area to Fort Bragg. It was Covid Time. I could not touch or hold my newborn granddaughter, but I could at least see her from a distance and marvel at her beauty.

By this time, Gary had been transported by ambulance to come home to die. His sister was also with us as well as daughter Laine, her fiancé Julian, daughter Jenn and granddaughter Nora. Son Garth and granddaughter Lyra spent a few days. It was chaos—a beautiful chaos that Gary thoroughly enjoyed until his last two days when the toxins of kidney failure took his brain hostage and rendered him unconscious.

***

I am grateful to have been with sweet Lilla to celebrate her first year of life. Yet lurking in the shadows was Gary’s absence. Also lurking was grief, that hideous monster I try so hard to avoid, yet revels in reminding me of that terrible time a year ago. I try, I really try to focus on the current good things, but during this one-year anniversary period most are overlayed with heartbreaking memories.

When I shared my panic attack experience with my therapist, she explained that what I’m feeling occurs at a cellular level. My mind can compartmentalize the events of a year ago and put them into perspective. But my body holds the trauma and gives the anniversary of Gary’s hospitalization and death the power to take me down, to transport me back to that time as if it is currently happening.

A year ago, I was in hyper-overdrive. My husband of 46 years, the father of my children, was dying. I didn’t have the luxury to feel the full weight of that trauma. A year later, my body reminds me. My body tells me it’s time. Time to fear I’m having a heart attack. Time to sit down and cover my face for the one-thousandth time and weep. It’s time to acknowledge that this was the worst, most horrendous period of Gary’s life, of my life, of my family’s life.